Rural And Community Hospitals – Disappearing Before Our Eyes

Over the last 10 years, more than 129 rural and community hospitals have closed their doors, with the highest number in 2019. The current COVID-19 pandemic is certain to accelerate this rate of insolvency, so it is important to revisit the role of these vital providers in their respective communities.

Are these hospitals community assets or simply another business? Are they similar to fire departments – there to serve the public and save lives? Or are they companies in a free market that have no accountability to local communities regarding decisions of services and sustainability?

Without answers to these important questions, the continued loss of these hospitals may jeopardize the health of rural residents and devastate communities across the country. It is vital to understand what can be done to avert the failure of these hospitals.

Background

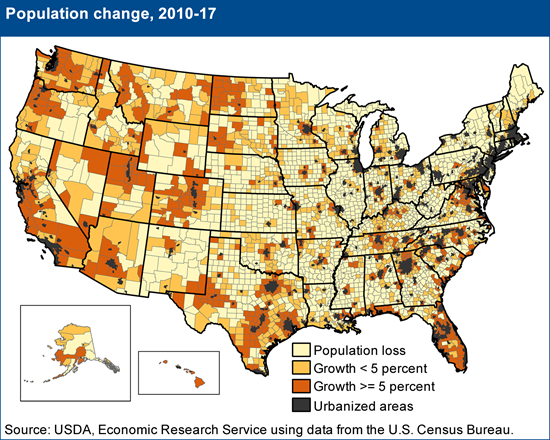

Community hospitals in America serve approximately 46 million residents of rural areas and 175 million people living in suburban and small metro areas.[1] However, significant shifts in population in these rural and suburban areas have resulted in significant impacts to rural regions.

Diagram 1

Outmigration weakens rural hospitals in three ways. First, the “left behind” populations are generally older and reliant upon Medicare or Medicaid, resulting in a higher cost of care with relatively lower reimbursements for local hospitals and other providers. Second, the local loss of physicians and nurses has made hospital staffing challenging. Third, because of the overall financial condition of most rural and community hospitals, the investments in new services, technologies, and facilities are limited, leaving the population underserved or unserved for many illnesses.

Despite the challenges, most rural hospitals outperform their non-rural peers in several areas of patient satisfaction and outcomes including lower readmissions and mortality rates, higher patient satisfaction scores, and important quality differences for common inpatient stays such as urinary tract infections, heart failure, pneumonia, and COPD-related illnesses. Rural hospitals also charge less for inpatient care on a case-mix and wage adjusted basis than urban hospitals.[2] The closures and subsequent decrease in local access to quality health care results in higher costs for all.

The COVID-19 pandemic has amplified the risk of financial failure for as many as 44 percent of America’s rural hospitals[3] and up to 25 percent of hospitals across the United States. Given the existing imbalance of hospital distribution based upon population, the possibility of hospital closures raises grave concerns relating to the health of people living in rural and smaller communities.

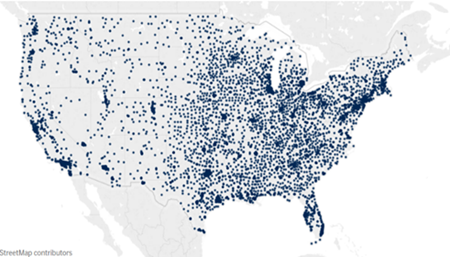

| Diagram 2 Map of Community Hospitals in United States: 5,198 Hospitals Data: 2018 AHA Annual Survey |

|

In order to understand the full impact of hospital closures, it is important to recognize that hospitals typically support communities much more than other businesses. They provide not only vital services in line with fire departments, police departments, and schools but also serve as economic engines. Even so, most hospitals are typically not the recipients of direct local or state tax funding as part of their regular budgets and therefore are in the challenging position of being required to provide public services while operating as a regular business.

In times of economic downturn, this situation places rural and community hospitals at a higher risk of failure. As a critical piece of the American health care delivery system, this group of hospitals needs to be reconfigured post-COVID-19 in order to continue making important contributions to the health and economic stability of the country.

COVID-19 considerations

The COVID-19 pandemic highlights the weaknesses and disparities in our country’s health care system. As the pandemic evolves, discussions will trend toward our health system and the review of what went right and wrong, including a re-think of our national health care structure.

Despite these debates, the need for health care outside of the larger cities, including during future national health crises and community catastrophes, will remain. As COVID-19 exacerbates rapid change in the health care sector, some organizations will adapt and survive. Unfortunately, many rural and community hospitals will be unable to change and therefore unlikely to survive. But even these hospitals may have options to preserve important parts of their health care and community value.

Immediate action required

Absent a clear and actionable recovery strategy and funding in addition to the CARES Act, most hospitals will face financial crisis within six months. This is especially true for hospitals with less than 90 days of cash on hand. Recent analysis demonstrates the inadequacy of these cash supplements in offsetting the combined negative impact of unbudgeted and excessive COVID-19 preparedness planning with lost revenue from the mandatory and abrupt halt to elective case volume and ambulatory services.[4] Unlike urban or “hot spot” hospitals, many rural and community hospitals have not seen a surge in COVID-19 patients and have not adapted operating costs to the reduced case volumes. Short-term survival will require decisive leadership beginning with tactical actions that must include the following:

| Clinical leadership | Utilize best practices for clinical care models

|

| Operational review | Reorganize operations

|

| Financial management | Build cash reserves

|

| Governance & strategy | Re-think purpose and strategy

|

Creating long-term value and sustainability

In addition to proactive management, the boards of directors or trustees of the institutions must know their fiduciary duties and hold management accountable for both today’s actions and future plans. Boards with limited experience in hospital operations or health care policy will need to become educated on their duties, risks, and decision-making responsibilities. Management, outside counsel, and other professionals may assist the board in fulfilling their fiduciary duties and providing appropriate services to the community.

Most importantly, struggling organizations also need to embrace the reality that the sun may have set on the days of “standing alone.” By acknowledging this accelerating trend, organizations will be able to pursue partnerships or join systems. This may mean considering alignments with larger systems that change the rural or community hospital from a full-service provider to a facility focused on high-demand and critical services. Non-critical and backup services can be obtained from a larger partner.

The pursuit of any option will require funding. Waiting too long may doom an organization closure. The fallout of closure includes the loss of care for patients, the loss of jobs in the community, the loss of businesses supported by the hospital, and suspicions regarding mismanagement. Now is the time to examine the role of these hospitals in their communities. Are they community assets, or are hospitals just another business that can close without much oversight?

In some states where significant oversight is provided, the closure of a hospital is hotly debated and challenged, requiring all stakeholders to craft a solution. This approach, while typically at taxpayer expense and relatively inefficient, does have a stabilizing effect that reaches beyond the walls of the hospital. Some states are considering legislation that will expand state attorney generals’ oversight of health care acquisitions and affiliations. While these actions may result in full vetting of potential transactions, such legislation may also limit options for smaller hospitals at a time when every source of funding must receive careful consideration.

In other states with less regulatory oversight, organizations may search for external parties to preserve hospital value. Such circumstances can allow strategic acquisitions by for-profit investors who generally bring needed capital and a business model that may preserve care. However, if changes fail, investors are typically less willing to continue underperforming operations, regardless of community needs.

Each approach has value, as well as clear advantages and disadvantages. Both offer the potential outcome of ensuring the survival of a community asset. Given the dramatic impact of COVID-19 on most states’ treasuries, it is likely that more troubled hospitals and health systems will look to investor-owned solutions rather than relying on state or local governments.

Regardless of capital options, communities will depend on their formal and informal leaders to navigate challenges with a manageable amount of disruption that hopefully results in better access to health care services.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted many weaknesses in our health care system. It is time for Americans to assert their highest values and priorities. If allowing our aging and poor in rural areas to die at higher rates than in non-rural areas is unacceptable, then allowing hospitals to close is not the answer. All Americans, regardless of where they live, deserve equitable care. We must revise our strategies and choose solutions with adequate funding and responsible partners that best align health care delivery with community needs.

About the authors

Mark E. Toney is a co-founder of ToneyKorf Partners, LLC, and an experienced leader in turnaround, revitalizing, and restructuring of hospital and other health care organizations.

Richard B. Becker, M.D., is a senior managing director of ToneyKorf Partners, LLC. He has more than 30 years of experience leading organizations in revitalizing and turnaround of hospital systems.

[1] Pew Research Center analysis of National Center for Health Statistics Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties.

[2] Michael Topchik, Rural Relevance 2017: Assessing the State of Rural Healthcare in America, (iVantage Health Analytics, 2017).

[3] Ayla Ellison, The rural hospital closure crisis: 10 things to know, (Becker’s Hospital Review, February 7, 2020).

[4] Richard Becker, M.D., Jim Porter, and Peter Yeh, Hospital Liquidity in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Impact and Mitigation Strategies, (ToneyKorf Partners, LLC, April 2020).